A sensitive soul that was prolific in painting, music as well as playwriting; a woman of South-American and Jewish descent, during the rise of Nazism in Germany in the late Twenties and early Thirties; an intellectual that took her profession of artist extremely seriously, despite lacking an academic education and a consistent trust in her own talent, Anita Rée was an artist whose tragic destiny silenced the memory of her work.

Born on Februay 9, 1885 in Hamburg, the second daughter (after Emilia) of Eduard Israel Rée, who descended from a wealthy Jewish family of cereals traders, and Anna Clara Hahn, a Catholic with Indian and Venezuelan origins, Anita Rée was raised as a Protestant and immediately inserted in the cultural circles of Hamburg.

Her father, who is described by Anita’s friends as a stocky, jovial man, had an ambition for the daughter to undertake a steady career, maybe in the family’s trade business, and unsuccessfully tried to avert Anita’s admission to the groups of some of the most prominent artists of her time.

He yet valued a worldly education of his children, and provided for lessons of piano and French.

The fatherly resistance to an artistic curriculum of the daughter was due not only to the economic uncertainty that came with having to rely on commissions -especially in times when the aesthetic taste was speeding towards Modernism-, but also to the absence of academic courses for women in the city of Hamburg.

In 1904, she first attempted to become a student of the Berlin based painter Emil Rudolf Weiss; however, her traineeship took off only with the enrollment at Arthur Siebelist’s studio. Siebelist was an exponent of the Hamburg Impressionists, whose method contemplated en plain air lessons during the summer, and workshops led in the atelier during the winter.

In the first works of these period, Anita Rée started adopting a leitmotiv that would subsequently become the stylistic hallmark of her self-portraits: her eyes pointing at the observer, often in a side glimpse, framed by a thick set of eyebrows, and her mouth relaxed in a rather serious expression. The aspect of the artist is not arranged to please the observer; it is instead a snap-shot stolen from hours of scrupulous self-examination in front of the mirror.

Her traineeship with Siebelist was fundamental for Rée to develop the first crucial roots of her network. It was during the training, that she met and befriended other artists including Friederich Ahlers-Hestermann and Franz Nölken, who would form the core group of the Hamburg Secessionists, and would assume a critical role in Rée’s conception of relationships.

The quality of Rée’s trait progressively distanced itself from the luminous, impalpable coats of Siebelist. She approached the views of masters such as Lovis Corinth, who held Impressionism as a fleeting trend, and despite discarding the rapid hatching of Impressionists, she preserved the massive use of color, as well as -occasionally- the support of photographic media.

With the confidence of Anita growing to an unprecedented low, Mr. Rée spurred the daughter to submit her portfolio to the painter Max Liebermann, to whom he was connected through another art celebrity, Aby Warburg. The latter’s brother, Max Warburg, led the Warburg Bank together with Anita’s cousin, Carl Melchior.

The visionary art historian addressed a recommendation to Max Liebermann, who in return sent a personal invite to Anita Rée, whom he met in his apartment in Pariserplatz 2, Berlin on January 7th, 1906 at 11 AM.

Pleasantly struck by the novelty of Rée’s hand, Liebermann prompted Anita to pursue her studies in Berlin, which she could not afford due to the prohibitive costs of the art schools in the Capital.

Hence, she carried on her practice from the frugal studio set up in her parents’ house, that reinforced the imagery of her craft as devoid of romanticization: being an artist was often a fatiguing, thankless, dull job, comparable to the physically demanding one of a workman, rather than the bright flights of fancy of an intellectual.

From that period, we have the B&W photographic reproduction of a portrait that shows the artist looking straight at the observer (or, as a figurative hint suggests, in the mirror), her head slightly reclined and wreathed with an elaborate braid, a window in the top right corner, that is a stratagem to nestle a landscape painting, and a still life arranged on the table. The Selbstbildnis im Atelier (1908 ca.) testifies the character of a well-read, Protestant artist, who had consumed an abundance of Flemish references: the flowers, symbol of a human life more ephemeral than the pictorial keepsake, and the books, proof of her artistic literacy, are staples of the Dutch still life Masters; and the reproduction of Rembrandt’s 1634 Self-portrait (which Anita had probably seen at the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, today flown into the Gemäldegalerie of the city) here represented in specular position, anchors the discipline of Rée’s self-analysis to the psychological fathoming of the Dutch painter.

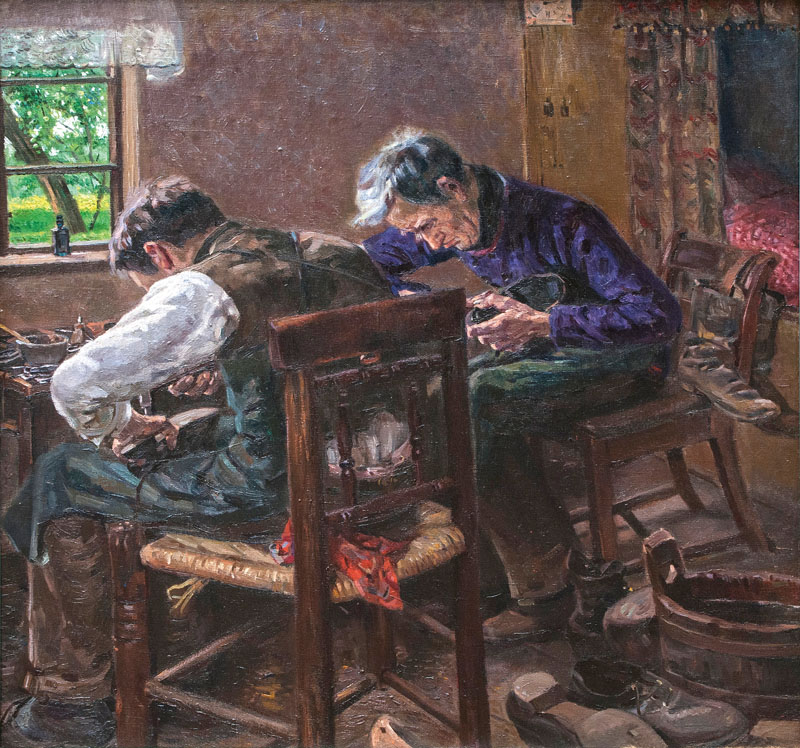

Atmospheres of wearing rigour persist in the painting Schusterwerkstatt in Hittfeld, which Anita Rée painted as a catharsis and encouragement after professors such as Leo von König and Wilhelm and Alice Trübner had turned down her application for private lessons.

Rée established in this work a clear link with one of Liebermann’s paintings that she had seen at the Berlin Nationalgalerie in 1906: Schusterwerkstatt in Dongen, an oil on canvas painted in 1881.

The two couples of shoemakers in the paintings betray two opposite sentiments around the concept of work.

Liebermann’s shoemakers are a young apprentice and his poised, imperturbable teacher. Their work encompasses the pleasure of passing on knowledge and continuously learning; their actions are complementary and lightened by the rays of sun coming through the window of a salubrious studio, almost as a metaphor of their Apollonian, disciplined practice.

Rée’s shoemakers are two men of the same age, consumed by the labor of an exhausting, repetitive series of tasks. Their action are not complementary: they rush towards the production of shoes, that pile up messily on the floor of a grim shack. The rational dignity of their job is sacrificed to the urge of scraping a living; the fire ignited by passion is a long-gone memory. If anything, Rée’s shoemakers could be a translation in color of Käthe Kollwitz’s denunciation of poverty.

Max Liebermann, Schusterwerkstatt in Dongen, oil on canvas, 80×64 cm, 1881, Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Courtesy Wikimedia

Anita Rée, Schusterwerkstatt in Hittfeld, oil on canvas, 90,5×89 cm, 1904, Auktionshauhs Stahl. Courtesy Auktionshaus Stahl

Soon enough, Rée was able to identify new mentors in her former classmates at Siebelist’s studio.

In 1910, Franz Nölken -for whom she also developed an infatuation- and Friederich Ahlers-Hestermann were openly receptive of the French trends, and drew Anita close to Cubism, Fauvism and the ideas of Cézanne.

The two Hamburg artists themselves had assimilated the French lessons by working in Henri Matisse’s studio throughout the year 1907.

This fellowship meant for Rée the validation of a newly found sharpness in her trait, which blended the aggressiveness of Expressionism with the measured reflection on volumes typical of Cézanne.

It also marked one of the most painful moments in Rée’s life: Franz Nölken grew increasingly distant and avoidant of Anita, becoming aware of her non reciprocated love, and he fled from Hamburg to take refuge in Westfalia.

The searing disappointment was channeled into the conviction that she still had to overgrow her provincialism; thus, Rée left for an educational residency in Paris, which might have lasted a few weeks or months.

She probably visited Fernand Légér’s studio in Rue de l’Ancienne, 13 in Paris; many geometrical sketches, probably taken during Légér’s classes of nude copy, reveal an attempt to destructure bodies into an ensemble of straight lines and curves. Other sketches of the same period (1912-13) suggest that she might have lingered in galleries and museums to absorb Cézanne’s way of illustrating external elements, such as clothes.

Back in Hamburg, Rée entertained herself and the other pioneers of the Hamburg Secession with proofs of concept inspired to Cubism.

During this phase of her career, she opted more frequently for watercolor. The choice of a new set of tools depended partly on the desire for imitation of the French school; partly, it was due to Rée’s genuine sake for experimentation and growth as an artist.

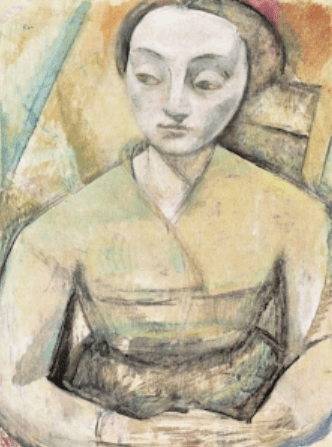

Agnes is one emblematic series of that period, that is for Rée the testing ground to showcase her knowledge of masterpieces such as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (Picasso, 1907), or the mannequin-like figures of Oskar Schlemmer and Pittura Metafisica, but also to reach a compromise with her own taste for Realism. In the three versions of the subject, Agnes, a maid employed at Rées, mantains her individuality of dignified woman and worker through the mutating, earthy backgrounds and flipped planes.

Anita Rée, Agnes I, oil on canvas, 70×64 cm, 1913, private collection. Courtesy The Athaeneum

Anita Rée. Agnes II, oil on canvas, 65,4×50,2 cm, 1913, private collection. Courtesy The Athaeneum

Anita Rée, Agnes III, oil on canvas, 60×51 cm, 1913, private collection. Courtesy The Athaeneum

1913 was also the year in which Rée was first featured in one of the exhibitions of the Hamburg Secession at Galerie Commeter. She participated with a Landscape With A Pond, a Still Life and a Building In The Monastery that are nowadays lost.

These paintings were, however, quoted in a 1936 chronicle by Gustav Pauli, a dear friend of Anita and director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle. He reminisced how these paintings, together with a légérian Self Portrait (1915) and two Ballerinas along the lines of Degas, made him first aware of Rée’s grounded talent, and also of her being doomed to oblivion: the poetic of the Hamburg Secessionists, so tightly clasped to the contemporary French avant-garde, couldn’t but become the tail-end of other movements, that already were popular in Europe on a larger scale.

Rée shared indeed with many of her colleagues a pro-European ambition. Their salons quickly transformed into unique laboratories of political engagement, as well as occasions of growing mutual fondness.

Ahlers-Hestermann would often host Anita in his studio, together with his Russian wife Alexandra Povorina -whom he had met in Paris in 1912-, and they would serve each other as free-of-charge models.

Both in words and in portraits, the couple described Anita Rée as ambitious, restless, hard-working and energetic, fierce, proud, irritable, inclined to exaggerate outbursts of exasperation; but also as generous, affectionate, intense, and capable of erupting in a silvery laughter that would light up the room.

Thanks to the friendship with Alexandra Povorina, we have been bequeathed with a manifesto of Rée’s ideal of art at that time. In a letter from July 23rd, 1916, Anita declared that she could no longer postpone the crossing of German Expressionism, whose impulsivity was far from the reflective qualities she appreciated in artists such as Picasso and Cézanne. She would later on withdraw these statements; but 1916 was still the time for Rée to assimilate the clear-cut outlines of the French contemporaries and the cold color palette of Derain, Picasso and, surprisingly enough, Van Gogh.

Anita Rée, Kranker Knabe, oil and charcoal on paper, 31,5×23,5 cm, 1915, private collection

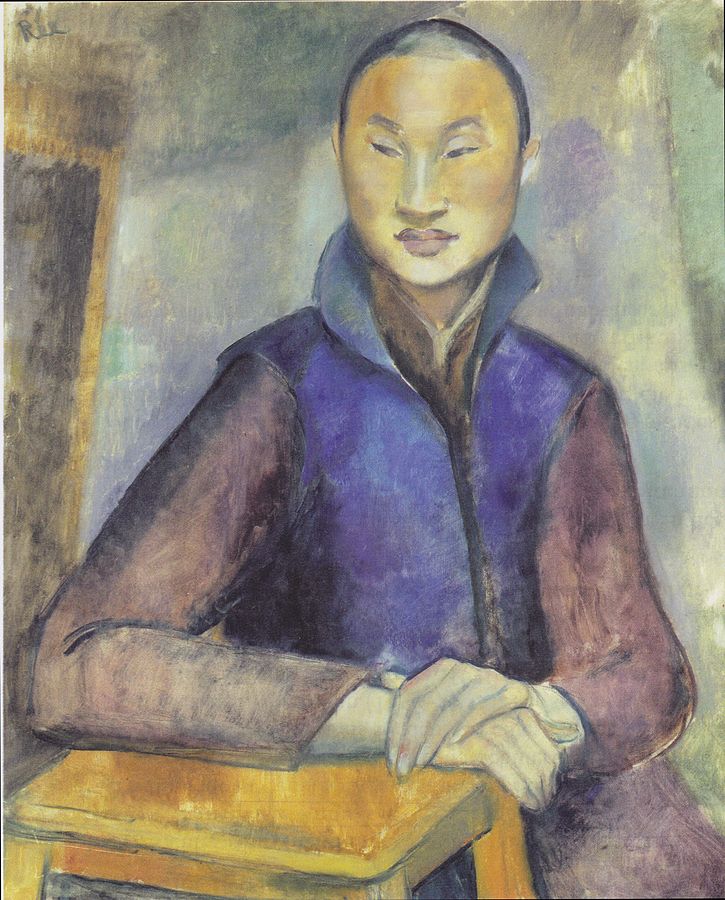

Anita Rée, Junger Chinese, oil on canvas, 75×60,5 cm, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, 1919

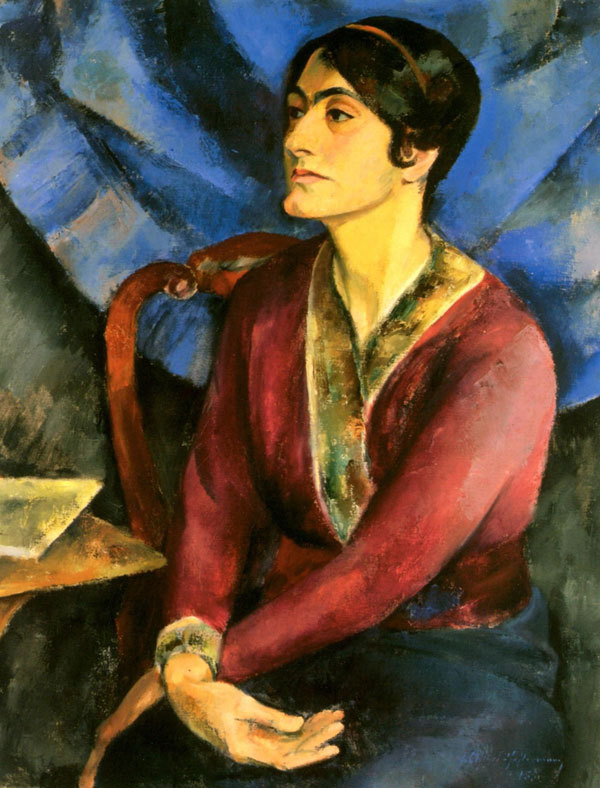

Anita Rée, Blaue Frau, oil on canvas, 90×69 cm, 1919, private collection

In these years, Rée corroborated her friendship with Gustav Pauli, who functioned as a joining link to the artistic Gotha of Hamburg. Within the frame of his cultural circle in Adolfstraße, Rée entertained conversations with Aby Warburg and Erwin Panofsky.

She also became acquainted with the circle of Richard and Ida Dehmel, and a disciple of the painter and man of literature Carl Hauptmann.

The latter intended to treat Rée as an equal: he invited her to concerts and lectures, praised her playwright Jacob -a subtly autobiographical work, that used the biblical figure of Rachel to celebrate the inexorable power of female friendships in a male dominated world-, and applauded the exotic, foreigner taste of her paintings.

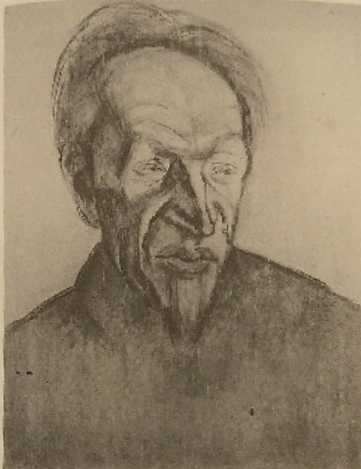

Nevertheless, Rée didn’t let the occasion of a portrait escape, to depict with sarcasm the self-referential arrogance of the intellectuals. Hauptmann’s physical traits are sculpted with angularity, his eyes looking downwards in an act of superiority, his fleshy lips semi-opened: the portrayed is on the verge of talking, perhaps interrupting the speaker’s argument, as if he assumed he had something more interesting to say.

Rée could afford a touch of biting satire here and there, because she was after all at her ease among artists, curators, writers and musicians. In the same years, she had the chance to portray the director of the Hamburg Philarmonie, Siegmund von Hausegger, and several musicians, such as the friend Ilse Fromm-Michaels.

Nonetheless, while her star was rising, the circumstances of her private life were somewhat unfortunate.

In 1917 her father died; at the age of thirty-two, Anita Rée was still a woman that hadn’t experienced any romantic relationship, which she was constantly yearning for; she lacked the recognition she envied in her male colleagues; financial independence was still a sore topic.

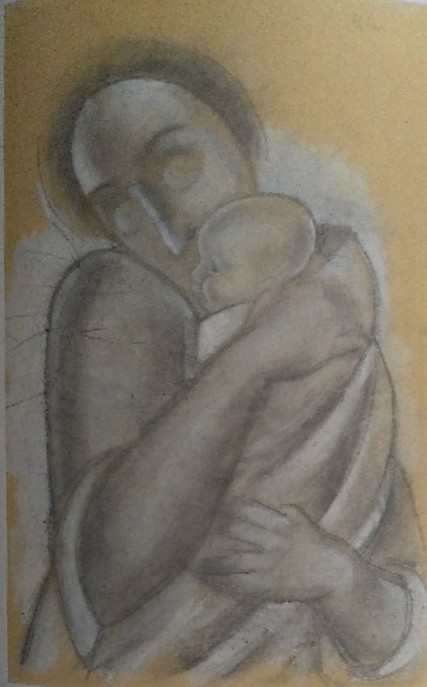

From 1917 and on, Rée introduced a subject in her paintings, that unveiled a desperate need for tenderness and human closeness.

Numerous paintings and sketches are illustrated with mothers holding their infants; many of them resemble Anita herself and the babies of her friends, squeezed in an almost morbid hug.

Rée’s friends often underlined how Anita found herself in the shoes of an unconventional woman, against her will. She made up for her loneliness by pouring her maternal instincts onto others’ children. And in these paintings, Anita’s soul is equally split into the two characters: she is both the inert babies, perpetually sick and depending on others for survival, and the resilient mothers, emaciated yet strong, stoically lifting the burden of the world upon their shoulders.

The Blaue Frau (see above) was so iconic for Rée’s poetic, that she kept it with herself until her death and it was universally recognized as a keystone of the Hamburg Secession.

Anita Rée, Mutter und Kind, charcoal and opaque white on pencil, 31,9×20,8 cm, 1915, private collection. Courtesy of Karin Schick, Anita Rée – Retrospektive, Prestel, München, 2015, fig. 63, pag. 181

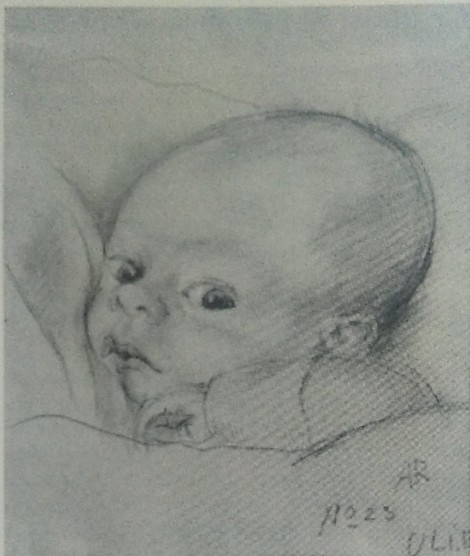

Anita Rée, Uli Burk, pencil, 29×22 cm, 1917, private collection. Courtesy of M.B., Anita Rée, (see quoted work), fig. 45, pag. 56

Anita Rée, Mutter und Kind, watercolor and opaque color on pencil, 32,7×24,6 cm, ca. 1915, private collection. Courtesy of K.S., Anita Rée – Retrospektive, (see quoted work), fig. 62, pag. 180

Rée’s toil paid off in the following years. She was represented in 1918 in an exhibition organised by Ida Dehmel at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Frauenbund zur Förderung deustscher bildenden Kunst; in 1919 at an exhibition in Kunsthaus Lochte; in 1920 at the Frühjahrausstellung der Hamburgischen Kunstlerschaft and was featured for the first time in an exposition abroad, at the Exposition internationale d’art moderne in Geneva, next to distinguished names such as Derain, Dufresne, Utrillo, Vuillard and Kokoschka.

In 1921 (as well as, subsequently, in 1928 and 1931) she opted out of the exhibition of the Hamburger Secession, as very few women were being showcased and, if anything, the free slots had been assigned to pieces from private collections by Franz Marc, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Alexej von Jawlensky, Vasilij Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. The group that had determined such a program for the 1921 edition would soon separate and reunite under the name of Hamburger Revolutionsexpressionismus.

What, instead, Rée commended in the 1921 edition and encouraged her fellows to maintain, was the introduction of musical appointments and the featuring of African artifacts, in the wake of the artists’ plea to emancipate from Western centrism.

1922 marked the beginning of possibly the happiest phase in Rée’s life.

Conjugating a wish for independence with reveries around furthering her visual culture with a travel to Mediterranean countries, Anita Rée left for Italy, where she would reside until 1925.

Already in the summer of 1921, Rée had tested the waters by venturing on a trip to Tirol, that filled her eyes with images of a simpler, yet fulfilling life. Memorable is the portrait of a Tiroler Bäuerin, where the feisty woman, who is identified as a farmer, stands out amid symbols of Catholicism (such as the rosary and the crucified Christ), letting the freedom of her spirit emerge.

Moreover, a boost of confidence came from her solo exhibit at Galerie Commeter and the participation in exhibitions in Travemünde, Stockholm and Helsinki.

In this particular phase, Rée felt more self-assured of her success as an artist, and could ease in a new chapter in Positano, in the South of Italy.

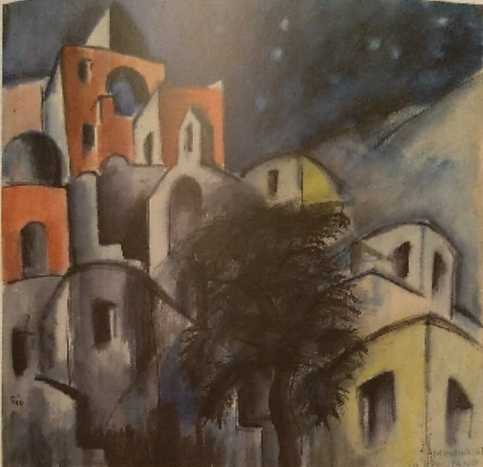

The Amalfi coast, drenched in sun, inhabited by small communities of amiable people whose life moved at a slower pace, took on a magical significance to Anita.

Rée was particularly charmed by the groups of houses shielded on the cliffs. She organized natural elements, such as the sea and the palms, into compositions where they stood in as guardians for mysterious Metaphysical towers. Arab-byzantine domes are the lids of prosaic buildings, such as mills, that reach monumental proportions and condemn human beings to minuscule dimensions; staircases are hidden behind a lattice of bare trees; human activities are bewildered and lost in the twists of an unwelcoming maze.

The exaggerated architectural structures stood for Rée as a symbol of her difficulties in overcoming some essential landmarks of life. Even the most insignificant structures appear in these paintings as intimidating and frozen in time under a melancholic spell.

Anita Rée, Mondnacht in Positano, watercolor, 43,5×46 cm, 1922-25, private collection. Courtesy of K.S. (see quoted work), fig. 84, pag. 117

Anita Rée, Mulino Arienzo, size and location unknown, 1922-25

Anita Rée, Weiße Bäume, oil on canvas, 71×80 cm, 1922, private collection. Courtesy Wikipedia

The Italian period coincided with the internalization of several styles: De Chirico, Morandi, Carrà were mingled by Rée together with Rosseau, Derain and the Neue Sachlichkeit.

Moreover, journeys to Calabria, Pantelleria, Assisi, Ravenna, Florence, Arezzo and Naples, in the company of a newly met crush, the librarian Christian Selle, and the friend Valerie Alport, offered to Rée the occasion to intertwine her art with the examples of the Old Masters, such as Giotto, Duccio di Buoninsegna, Piero della Francesca and Botticelli.

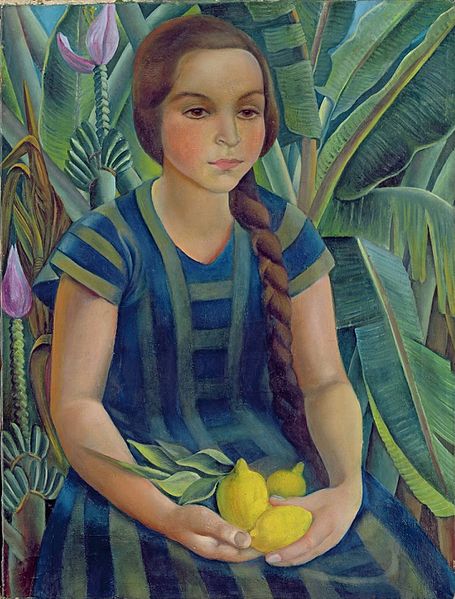

The faces met along the Italian pilgrimage were captured by Rée with a hint of exoticization. Many of the portraits, including her own, have Arabic traits and are drawn as if they were weary for the scorching sun, or inebriated by the Dionysian bliss of a simple life, in harmony with nature and not yet polluted by the same rigidity of Northern countries.

In the Selbstbildnis auf Pantelleria, Rée portrayed herself aloof, her skin and her hair camouflaged with the colors of the background. In the Halbakt vor Feigenkaktus, the model’s breasts emulate the shape of the juicy fruits on the succulent. Teresina‘s dress replicates the twine of the lush greenery behind her.

Above all, stands a desire of fusion with the environment and the euthanization of her cumbersome ego.

Anita Rée, Selbstbildnis auf Pantelleria, oil on canvas, 56,5×59,5 cm, 1924-25, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Courtesy of AKGimages

Anita Rée, Halbakt vor Feigenkaktus, oil on canvas, 66×53,5 cm, 1922-25, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Courtesy of Hamburger Kunsthalle

Anita Rée, Teresina, oil on canvas, 80,5×60 cm, 1925, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Courtesy of Wikipedia

Once back in Hamburg, these paintings determined some of Rée’s biggest economical and critical fortunes. Teresina was purchased by Gustav Pauli for it to be exhibited in the Hamburger Kunsthalle; Halbakt vor Feigenkaktus was bought, together with a Paar and the Römerin auf Goldgrund, by Max Warburg.

At her comeback in Hamburg, Rée found that she hat built herself the reputation of one of the most talented artists in Germany.

In 1926, Galerie Commeter dedicated her another solo exhibition, focusing on the nucleus of works from Positano. Despite benefiting from the consensus around her maturity as an artist, Rée discovered that the common feeling was that the prices of her paintings were too high, which produced a feeling of discrimination and lack of understanding, that would obsess her for many years to come.

Other junctures helped to increase a sense of excruciating loneliness.

She, in fact, had to give up on the studio at the parents’ house, and thus began for Rée a series of quick relocations at other people’s apartments.

The hard-earned independence of the previous months was fading, as well as the momentum of her work routine. Furthermore, in late 1925 she was reached by the news that Christian Selle was getting married, which was also a cause of the interruption of their epistolary exchange.

The coup de grace was the break with the Hamburg Secession, due to the refusal of her painting Weiße Nussbäume at the 1928 edition of their exhibition.

At the age of 41, Anita Rée suffered the blow of depression: without the solace of a family of her own, nor financial security, she started suffering from skin rashes and days of catatonic state. It was at this point that she started meditating on the possibility of suicide.

Agnes Holthusen, one of Anita’s doctors and closest friends, reunited a circle of women of culture around the painter, also to try to lift her spirit; but her testimony reveals how Rée was in a dreadful state, and her conceited, despotic, ill-tempered attitude turned valuable connections away.

In the years 1926-1930, Anita Rée fully appropriated the language of the Neue Sachlichkeit to run a merciless analysis of her relationships.

Disappointed by the elitism of the art community in Hamburg, she portrayed some of her friends as frigid individuals, either alone, or surrounded by things instead of people. Politics had without a doubt started to play a decisive role in granting her admiration, as the popularity of Nazism was rising, and Rée suddenly found herself having to justify her Jewish and foreign ancestry.

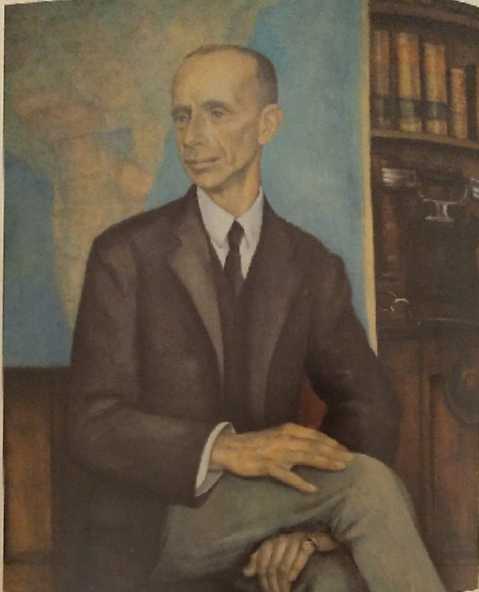

With hindsight, the Bildnis Wilhelm Burchard-Motz looks sadly prophetic.

Burchard-Motz was the Senator for Trade, Shipping and Industry of Hamburg from 1925 to 1933. In the past a national-liberal lawyer, he then became a leading figure of the NSDAP.

Anita Rée became the chosen family painter thanks to his wife Helena. Before she would knew that Burchard-Motz had exacerbated his positions towards Nazism, Rée portrayed him as a well groomed man, that appeared somewhat older than his actual age. The expensive decoration in the background, together with the map, contrasts with the dullness of his gaze, the banality of his traits and the discomfort of his posture: it is ironic that Burchard-Motz exhibited with pride in his office what he believed was a celebratory portrait, but clearly looks more like the caricature of a bureaucrat and a social climber.

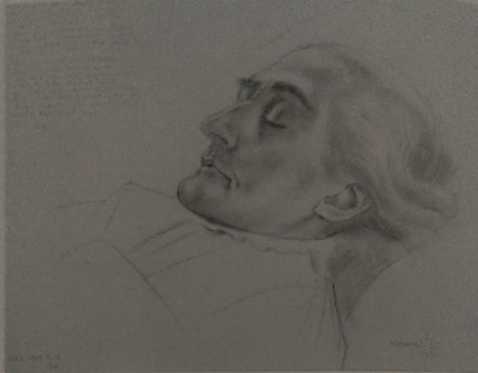

On December 3rd, 1930, Clara Rée, Anita’s mother, died of tuberculosis. The loss of her mother caused in Anita the worsening of her depression, and a stronger desire to be dead and finally free from any sorrow.

The portrait of the mother on her deathbed is uncannily resembling of Anita herself. The quick charcoal sketch frames the pointy profile and the long, scattered hair with a poem:

Was dann nach jener Stunde

G.B.

sein wird, wenn dies geschah,

weiß niemand, keine Kunde

kam je von da,

von der erstickten Schlünden,

von dem gebrochenen Licht,

wird es sich neu entzünden?

Ich meine nicht.

Doch sehe ich ein Zeichnen:

Über das Schattenland

aus Fernen, aus Reichen

eine große, schöne Hand,

Die wird mich nicht berühren,

das läßt der Raum nicht zu:

doch werde ich sie spüren

und das bist du.

(Translation: What will be after that hour/ when this has happened/ nobody knows, no knowledge/ ever came from there/ will it re-ignite again/ from the choking throat/ from the refracted light?/ I don’t think so./ But I do see a sign:/ beyond the land of shadows/ from afar, from a vast place/ a big, beautiful hand/ that won’t touch me,/ the distance won’t allow it:/ but that I will feel/ and that it’s you.)

The portrait of the mother comes across as a baleful omen when compared with Rée’s best-known Selbstbildnis of 1930.

In this self-portrait, Rée captured with touching honesty the essence of a woman in her forties, who clung onto her art to survive the struggles for the preservation of her mental health, her material means and the meaning of life itself.

In this painting, Anita looks straight at the observer from upwards, as if she was staring at her reflection in a puddle, like a contemporary Narcissus. However, the sentiment exuding from her face is not self-satisfaction, but genuine curiosity and an air of fear.

It is a testament that seizes Rée’s cast-iron discipline in self-analysis. She was not scared to sound the abyss of her own conscience out, despite this practice never paid off with the defeat of her own frailty.

Her face stands out from a golden background, that recalls that of hieratic Byzantine icons. She appears naked with her arms crossed in the shape of a crucifix; exactly like Christ, Anita accepted the hard task of being herself and is ready to die loyal to her mission. It might mean passing by in complete solitude, but it also means gifting humankind with necessary anti-conformism.

Anita Rée could temporarily recover from her depression by investing her energies in monumental projects in the city of Hamburg.

Fritz Schumacher, the director of the commission for public works in Hamburg at the time, commissioned a huge program of architectural enhancements, that would be decorated by the in-vogue artists of the city.

In 1932, the outcomes of that golden era of public art were published in the brochure 24 Wandbilder in Hamburger Staatsbauen, which sealed the ideal of that project as belonging to the tradition of Légér, Jeanneret, Ofenfant, but also Schlemmer and the frescoes of the Old Italian Masters.

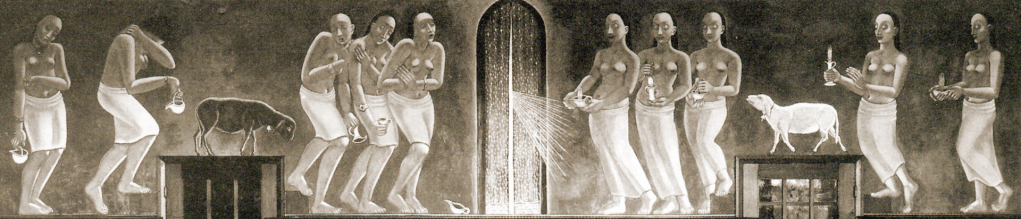

Anita Rée was put in charge of three locations: the conference hall of the Berufsschule in Uferstraße, the gym of the Oberrealschule für Mädchen in Caspar-Voght-Straße and the adiacent St. Ansgar-Kirche.

Ever since the first project, Rée encountered resistances whose motives could be traced back in political and social discomfort.

Germany was about to fall under the conservative aegis of Nazism and Anita Rée, despite having been raised as an Evangelical German, was already scorned as a foreigner Jew.

The iconographic program she had conceived for the hall in Uferstraße had to be adapted to the teachers’ room, where her commission had been relegated, in order to avoid a scandal for the presence of nudity in a public setting.

As it is possible to read from the correspondence of that period, the Biblical theme of the Ten Virgins, chosen by Rée, was actively opposed by the teachers of the all-female professional school, at first with ploys intended to discourage Rée’s continuation of works, then with open signed letters at the attention of the Baubehörde.

Nevertheless, Schumacher, Pauli and other members of the commission for public work defended and supported Rée, who could bring to term the production of the fresco in the teachers’ room.

Leaving the critics astonished for the ease with which she could master the technique of fresco, kneading the pigments with casein and nimbly spreading them on the walls, from a precarious station consisting of a chair mounted on a banister, Rée painted the theme of the Ten Virgins, whose versatility allowed her to comply with the pedagogical purpose of the work, without having to give up on satire.

If, on one hand, the Wise Virgins could serve the schoolers as an example of readiness and docility, Rée’s sympathy tended towards the group of the Foolish Virgins who, exactly like the women in the newly born Republic of Weimar, had to resort to their intelligence and work abilities to make it in a new order.

The Virgins are portrayed in a style that puts Masaccio, Mantegna and Piero della Francesca near to Gauguin.

The Foolish Virgins, distinguished by a short skirt that signals their amorality, have richer individualities compared to their wise peers: in the first instance, they are aware of their fallibility, and they react to it with shame, sadness, grief, regret, and angst. They don’t feel the same monolithic, superficial contentedness of their friends, because they did have to deal with who they are.

Some critics even led to conclude that the Virgins are self-portraits of Anita herself.

The lambs, perfectly located on the architectural elements of the doors, also show Rée’s most authentic propensity: the sinful lamb looks down and inwards, while the lawful one looks upwards, in a haughty attitude.

The second of Rée’s public commissions is the only one which is still currently visible.

The theme chosen for the gym of the Oberrealschüle für Mädchen (nowadays Balletzentrum) is Orpheus and the animals, which Rée judged as adequate for a place that had to welcome music and movement.

Unlike the unfortunate incident at Uferstraße, this one was for Rée an extremely positive experience.

Both the director of the school and the student were amused by the naturalistic subject and left Rée the freedom to experiment with diverse styles.

Drawing inspiration from the Ancient Egyptian parietal painting, Persian miniatures, textile manufactures and the mosaics she had seen in her travels to Ravenna, Rée brought on the walls of the school a rather new iconography, that had been previously introduced in Hamburg by Fritz Saxl and Aby Warburg.

In Rée’s work, exotic animals are paired with domestic animals and creatures born from her own fantasy.

The animals, depicted in elegant and light leaps, are more peaceful the closer they get to Orpheus, who in turn appears as a scared child. Once more, nothing is left to chance, instead, an exquisite ambiguity can explain the layered meanings of the iconography.

Having as a reference the Paleochristian Catacombs, Orpheus is a Christological figure, able to tame vile instincts; at the same time, it is an image of peace -or at least, of an established covenant, that was for Rée a vanishing dream.

An interesting fact: the frame is entirely composed of deers, Reh in German, hiding in a riddle the signature of the author.

The last public work that Anita Rée did in Hamburg, and that was a watershed for her own personal resolutions, is the Triptych for the St. Ansgar-Kirche.

The episode of this painting determined, in fact, the final escape of Anita Rée from Hamburg, as it had become impossible, even for her patrons, to defend her work from the official reprimands of Nazism, that judged Judaism “of blood” a crime as serious as Judaism “of culture”.

The Tryptich of St. Ansgar had two sides. When closed, it showed a new declination of the theme of the Ten Virgins, picked in this case to invite the audience to have faith in times of historical turmoil; when opened, it displayed The Last Supper in the center and The Entrance in Jerusalem and Judas’s Kiss on the sides.

In all the portions, Jesus is portrayed as a young adult with Arabic traits and no beard. The bodies are painted as extremely geometric, as if they were made of the same material of the Italian looking cities on the background, but they still fuse in gestures of regrettable intimacy that illustrate the tragic nature of the events.

Judas’s kiss, as intense as Rée’s previous paintings of mothers and children, surprises Christ in an aghast lack of consent; John falls asleep in the arms of his leader, foretelling the torpidity in the garden of Gethsemane.

References to Leonardo da Vinci, Dirk Bouts and Ambrogio Lorenzetti crumble in a rather ironic effect, that became the ultimate cause for Rée to leave Hamburg in order to avoid more severe repercussions.

The last years of Anita Rée are marked by an unbearable condition of temporariness and a net rift with her previous life.

Unable to continue residing in Hamburg, Rée could be hosted for a while by the Scharlach family.

In July, when selling her paintings no longer sufficed to procure her a livable sum, she accepted the offer of an organization for the mutual help among artists and fled to Sylt.

If until then Anita was remembered by her friends for having some bizarre self-care habits, such as extravagant clothing, eating raw potatoes or eggs with their shell, the chaos started communicating to her working habits, and she hid all of her works in the cellar of the Kunsthalle, while keeping on painting on cardboard and diluting old tubes of color until the very last drop.

In addition to straitened circumstances, Anita Rée was saddened by the departure of Carl Vorwerk -her latest infatuation- for Chile following the Nazi persecution; the climate and the diminished social life that she could rely on while in Sylt, which was far from being exempt from the poison of Nazism; the paralyzing inability to work in such conditions, that eventually led to spiraling depression and suicide.

On December 12, 1932, Anita Rée took her life by ingesting a lethal quantity of Veronal. An excerpt from a newspaper, reporting the chronicles of a banker committing suicide with the same drug, was found in Rée’s address book, adding up to a series of proofs that indicate how Rée had meditated before on ending her life.

In a letter of December 2nd, 1933, she wrote to her friend Fridjof:

Ich kann mich in so einer Welt nicht mehr zurechtfinden und habe keinen anderen Wunsch, als sie, auf die ich nicht mehr gehöre, zu verlassen. Welchen Sinn hat es – ohne Familie und ohne die einst geliebte Kunst und ohne irgendeien Menschen – in so einer unbeschreiblichen, dem Wahnsinn verfallenen Welt weiter einsam zu vegetieren und allmählich an ihren Grausamkeiten zugrundezugehen?

Anita Rée to “Fridjof”, December 2nd, 1933

(Translation: I can no longer find my way in such a world and I have no other desire than to leave what I no longer belong to. What is the point of keeping on vegetating alone – without family and without the once beloved art and without any human being – in such an indescribable, insane world, and gradually perishing from its cruelties?)

The last works of Anita Rée move from a frenzied variety to, eventually, a rarefied place of peace.

Two series, in particular, are the touchstones of the mental state she was experiencing through the last months of her life.

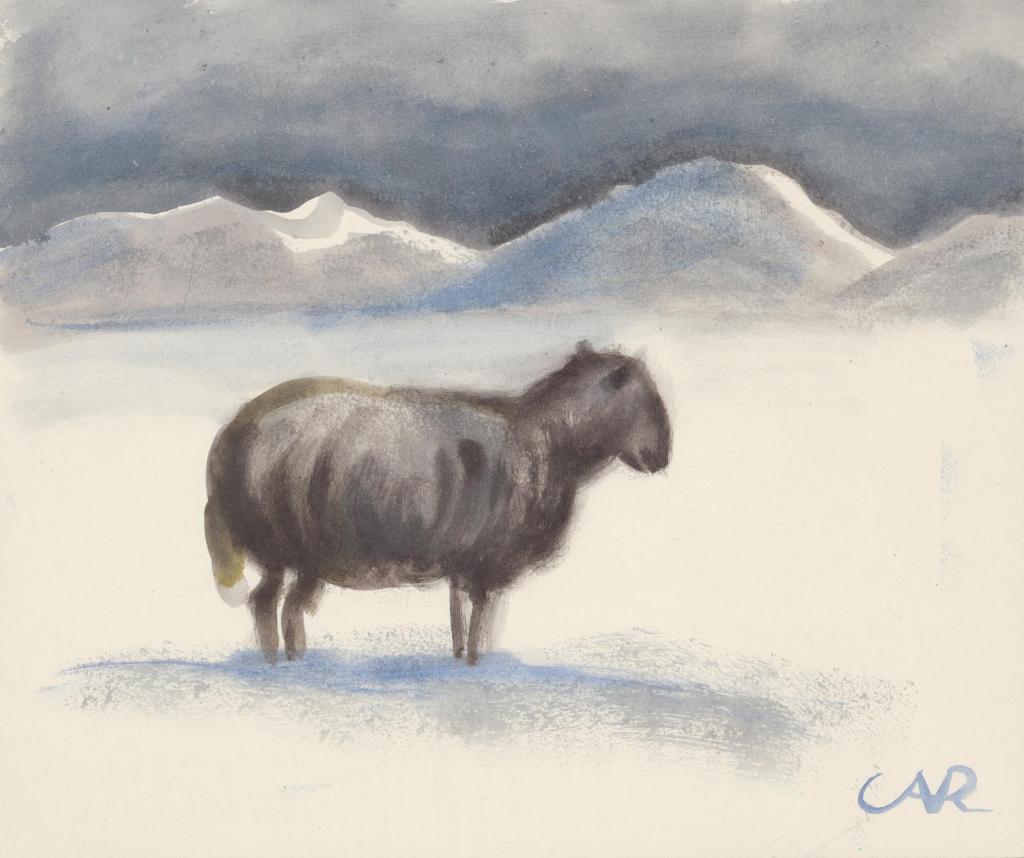

One is a series of small paintings, rendered through the essential color palette of Sylt winters, in which Rée tenderly draws sheep and calves, caught in the vulnerability of their birth, or sticking together in groups while in the meager pastures covered in snow.

Unlike herself, in these paintings the animals still belong to a group, and preserve the Christian innocence she had seen being swept away by Nazism. Like herself, the cubs in the paintings were born to suffer and leave the Earth forgotten.

Anita Rée, Schafe im Schnee, watercolor on paper, 39×49 cm, 1932-33, private collection. Courtesy Catplus

Anita Rée, Schafe, watercolor on paper, 25×29,5 cm, 1932-33, private collection. Courtesy Hamburger Kunsthalle

Anita Rée, Neugeborenes Kalb, pencil on paper, 22,5×28,5 cm, 1932-33, private collection. Courtesy Artnet

The second series is the study of dunes, conceived as heavenly oasis and obsessively replicated even on sandwich paper scraps.

The color palette was periodically sanded until it got reduced to a core of two-three earthy pigments, that induced Rée to refer to these paintings as “lunar landscapes”.

In the last versions, these dunes included other elements such as rainbows or lighthouses, a remote reminder of the art, that led Rée through times of despair.

Anita Rée, Oase in Kampen, watercolor on paper, 38×47 cm, 1933, private collection. Courtesy Wikipedia

Anita Rée, Oase mit Regenbogen, watercolor on cardboard, 27,5×30 cm, 1933, private collection. Courtesy Randomhouse

Anita Rée, Leuchtturm mit Zaun und Meer, watercolor on paper, 39,9×49 cm, 1933, private collection. Courtesy Hamburger Kunsthalle

Newspapers first reported the death of Rée on December, 13th, 1933, but only after the cremation had already taken place.

Hamburg-based newspapers didn’t make any mention of Rée’s death at all.

Gustav Pauli pronounced a farewell speech the day of her funerals, attended only by a few intimates, putting a stress on how few artists after Anita would have been able to equal her talent, despite having a more favorable destiny.

In her will, Rée indicated that she wanted Heinrich Theodor Beine, manager of her finances, to inherit her whole collection and not to mention the estate to anybody.

However, her brother-in-law, Heinrich Welti, was able to start a legal clause and retaliate, acquiring the full inheritance and proceeding to sell most of the pieces to private purchasers.

The only clause in the will that he respected was not to organize a post-mortem exhibition.

Rée’s burial site was dismantled in the 1980s, to make room for another deceased.

A commemorative stone was finally raised in 1995 in Ohlsdorfer Friedhof, in Hamburg.

Seen the contribution given to the Hamburg Secession, as well as the profound connections with intellectuals that she developed throughout her whole life, it is hard to explain why Anita Rée was so little remembered after her death.

It is possible that many factors converged in making her rather unpopular after she had passed away.

As a woman in a male-dominated branch, as an exponent of the Christian bourgeoisie that did not want to be associated with the Jewish community -and yet was, in her spite: in 1937, her works were already exposed among those of the “Degenerate artists”-, as a suicidal victim and as a person with poor mental health, Anita Rée was doomed to bring many stigmas on her persona even after death.

The research led in recent years has brought to light a woman and an artist whose personality reverberate vividly not only through her production, but also through her private letters and diaries.

Like the undetermined soul sung in the third of Gustav Mahler’s Rückert Lieder, Anita Rée’s offer to art resonates as the selfless donation of a woman whose only fault was to be and feel misunderstood.

The last known photograph of Anita Rée captures her alone, staring at the sea opening in front of her eyes on the bare beach of Sylt.

She is smiling, despite the bitterness harboring in her heart. In just a few days from when that picture was taken, she would be let free.

Plus qu’ennuyée

Marie Laurencin, Le calmant

triste

Plus que triste

malheureuse

Plus que malheureuse

souffrante

Plus que souffrante

abandonnée

Plus qu’abandonnée

seule au monde

Plus que seule au monde

exilée

Plus qu’exilée

morte

Plus que morte

oubliée

Sources

- Kathrin Burseg, „Ich habe keinen anderen Wunsch, als die Welt zu verlassen“, resonanzboden.com, September 22nd, 2015

- Maike Bruhns, Anita Rée, Verlag Verein für Hamburgische Geschichte, Hamburg, 1986

- Maike Bruhns, Jewish Art? Anita Rée and the “New Objectivity”, jewish-history-online.net, last consulted on March 23, 2020

- Hildegard and Carl Georg Heise, Anita Rée, Hans Christians Verlag, Hamburg, 1968

- Karin Schick, Anita Rée – Retrospektive, Prestel, Munich, 2017

Absolutely beautiful article about an artist whose work takes my breath away. I thought you might like to see this poem, inspired by one of her paintings.

https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1A2LffZDTh/?mibextid=WC7FNe

LikeLike

You did Anita Rée justice with this beautiful poem, one that encompasses fully her loneliness, her otherness, her sensibility and her brilliance. Thanks so much for sharing this with me ❤️

LikeLike